Financial inflows for Ukraine

New research argues that early, well-governed foreign capital inflows are central to Ukraine’s reconstruction and convergence.

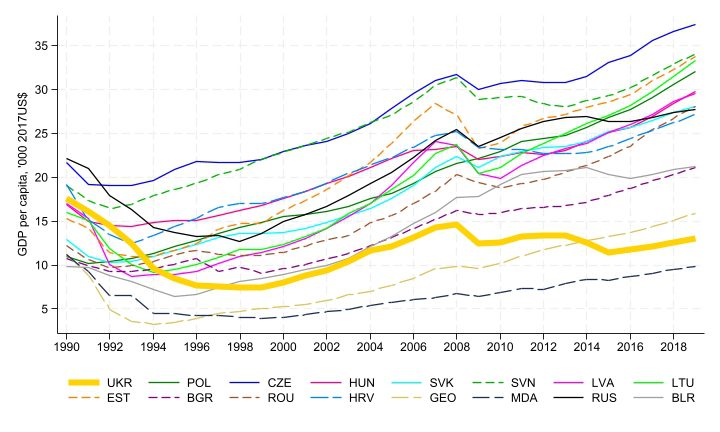

New research by Yuriy Gorodnichenko and Maurice Obstfeld examines how foreign capital inflows can support Ukraine’s reconstruction after Russia’s invasion. Ukraine faces a rare combination of challenges: a long-run decline in its capital stock, extensive war damage to housing and infrastructure, and continued large-scale emigration. Figure 1 of the paper, which traces real GDP per capita since 1991, shows Ukraine falling far behind many of its post-communist peers and motivates the search for a credible growth strategy. The experience of Eastern European countries that joined the EU and NATO suggests that sustained investment, anchored by institutional reforms, can deliver rapid income growth and convergence.

Figure 1. GDP per capita since the collapse of the Soviet Bloc. Source: Penn World Tables.

The authors combine a historical review of capital flows into post-communist Europe with three illustrative growth models tailored to Ukraine’s circumstances. Their historical analysis shows that countries which entered the EU and NATO attracted substantial inflows of foreign direct investment and EU structural funds, whereas non-members such as Ukraine and Moldova relied much more heavily on remittances. The former group experienced higher capital intensity, faster productivity growth and milder population decline. Notably, the credible prospect of accession was often enough to prompt early investment: a clear example is the surge of FDI into Czechia well before its formal EU entry. The authors argue that similar anticipatory effects could operate for a westward-facing Ukraine.

The theoretical analysis develops three simple but distinct models. One emphasises the high marginal product of capital generated by Ukraine’s low initial capital stock. Other highlights how additional capital can serve as collateral, relaxing external borrowing constraints and enabling further foreign finance. A third illustrates how capital deepening raises wages and can encourage the return of Ukrainian workers now living abroad. Across all models, complementary mechanisms mean that market forces alone are likely to generate over-consumption and under-investment, because private agents do not fully internalise the long-term benefits of a larger capital stock.

To address this under-investment, the authors show that a consumption tax that begins high and declines over time can tilt resources towards investment during the crucial early reconstruction years. In their framework, a permanent investment subsidy—or equivalently a permanent wedge discouraging consumption—may also be justified to correct persistent distortions. Although human capital remains essential for long-run growth, the models underscore that physical capital is more readily collateralised and can therefore unlock foreign borrowing more rapidly in the short run.

The paper offers indicative estimates of Ukraine’s post-war investment needs and feasible inflow volumes. The authors estimate that Ukraine will require at least 40 billion US dollars per year in external investment during the first decade after large-scale hostilities cease. Roughly half of this sum would replace destroyed assets, while the remainder would prevent further divergence from EU peers and support early convergence. This envelope implies capital inflows of around 20 per cent of Ukraine’s pre-war GDP. Historical experience summarised in Figure 21 suggests that, following major conflict, investment shares can rise from around 10–15 per cent of GDP to more than 20 per cent within five years. With strengthened governance and procurement, the authors argue that Ukraine could absorb similar investment rates without excessive cost inflation.

The distribution of investment matters for both economics and politics. Workers stand to gain through higher wages and improved employment prospects as investment rebuilds manufacturing capacity, housing and infrastructure—especially if these improvements induce a meaningful share of the roughly six million Ukrainians currently abroad to return. Yet liquidity-constrained households could face short-run costs if higher consumption taxes are used to finance investment. The authors therefore note that any tax-based rebalancing towards investment would need to be paired with targeted social support for vulnerable groups.

The study is careful to acknowledge risks. Large inflows can finance consumption instead of investment, fuel corruption and waste, or trigger boom–bust cycles if governance is weak. Heavy reliance on loans rather than grants risks leaving Ukraine with a high external debt burden that could deter private investors. Domestic financial markets remain shallow, with low deposit ratios and limited non-bank intermediation, meaning that mobilising substantial domestic savings will take time. Reforms to strengthen the rule of law, improve public procurement, and deepen the financial sector are therefore essential to ensure that foreign capital is used effectively.

Overall, the paper argues that early, sustained and well-governed foreign capital inflows offer Ukraine its most realistic pathway to rapid reconstruction and eventual convergence with its EU neighbours. For Ukrainian policymakers, this implies prioritising reforms that raise investment, attract reliable external finance and reduce uncertainty for investors. For international partners, it underscores the importance of early, predictable and grant-heavy support designed to catalyse—rather than displace—private investment.

You Only Live Twice: Financial Inflows and Growth in a Westward-Facing Ukraine

Authors:

Yuriy Gorodnichenko (University of California – Berkeley)

Maurice Obstfeld (University of California – Berkeley and Peterson Institute for International Economics)

(paper presented at the 1st Economic Policy: Papers on European and Global Issues Conference)

Watch the recording of the session

Downloads

Discussants’ slides