Financial Repression under Sanctions

New research finds that currency-market financial repression is not an effective stabilisation tool and is used mainly for redistribution or fiscal extraction.

Tariffs, trade wars, and financial sanctions have re-entered the policy toolkit, prompting governments to revisit “unconventional” measures such as FX interventions, capital controls, and financial repression. This paper asks when policies that deliberately depress the return on foreign-currency assets held by residents can support stabilisation under sanctions and capital-flow shocks, and how they compare with standard macroeconomic tools. The analysis focuses on currency markets, where sanctions often restrict access to foreign assets and households have strong motives to hold foreign cash or deposits.

Oleg Itskhoki and Dmitry Mukhin develop a small open-economy model with sticky prices and segmented FX markets, in which only the government-controlled banking sector can transact internationally, while households hold foreign-currency deposits for both consumption smoothing and non-pecuniary liquidity benefits. Policy instruments include conventional fiscal and monetary tools, FX interventions through official reserves, and financial repression via a return wedge on FX deposits. The authors extend the model to incorporate household heterogeneity and use a calibrated version to interpret Russia’s policy response following the 2022 invasion of Ukraine.

The central theoretical result is that in a representative-agent economy, financial repression is never part of an optimal stabilisation package. When FX reserves are available, the first-best combines inflation targeting to address nominal rigidities with FX interventions that fully accommodate shocks to household demand for foreign currency. By supplying foreign assets out of reserves, the government can keep the real exchange rate and import volumes on their efficient paths while allowing households to hold their preferred stock of FX balances at the world interest rate. Repression only reduces welfare by forcing households to hold too little foreign currency.

A second key finding is that repression is not justified as a second-best tool when FX reserves are scarce or frozen. In this scenario, the economy must allocate a limited inflow of foreign currency between imports and household savings. The exchange rate already reflects this trade-off, meaning households internalise the trade-off between using foreign currency for saving versus importing. No externality remains for repression to correct, and tightening FX returns introduces additional distortions without improving aggregate outcomes. Although repression can mechanically temper depreciation, it is welfare-reducing both with and without FX interventions.

Its role changes once household heterogeneity and fiscal constraints are introduced. If a fraction of households are hand-to-mouth workers who earn only domestic wages and do not save, an increase in FX demand by richer and financially-sophisticated households can depreciate the exchange rate and raise import prices. Some repression can then limit FX hoarding by savers and leave more foreign currency available for imports, redistributing real income towards liquidity-constrained households. For a utilitarian planner placing sufficient weight on these households, a positive degree of repression can raise welfare, even though aggregate quantities remain unchanged relative to the representative-agent benchmark.

A further motive arises from public finances. With downward-sloping household demand for FX assets, the government can act as a monopolistic supplier of FX deposits and extract seigniorage by lowering their return below the world rate. The authors characterise the seigniorage-maximising degree of repression and show how temporary easing can engineer a real depreciation that boosts fiscal revenues from the export sector, at the cost of higher consumer-price inflation. Tightening repression has the opposite effect. These intertemporal trade-offs affect the timing, but not the present value, of fiscal revenues.

The authors then use a calibrated version of the model to interpret Russia’s rouble–dollar exchange-rate dynamics in 2022–24. The freezing of roughly half of Russia’s foreign reserves (about one year of imports) is modelled as a permanent fall in net foreign assets, and the implied FX-demand shock is recovered to match the exchange-rate path.

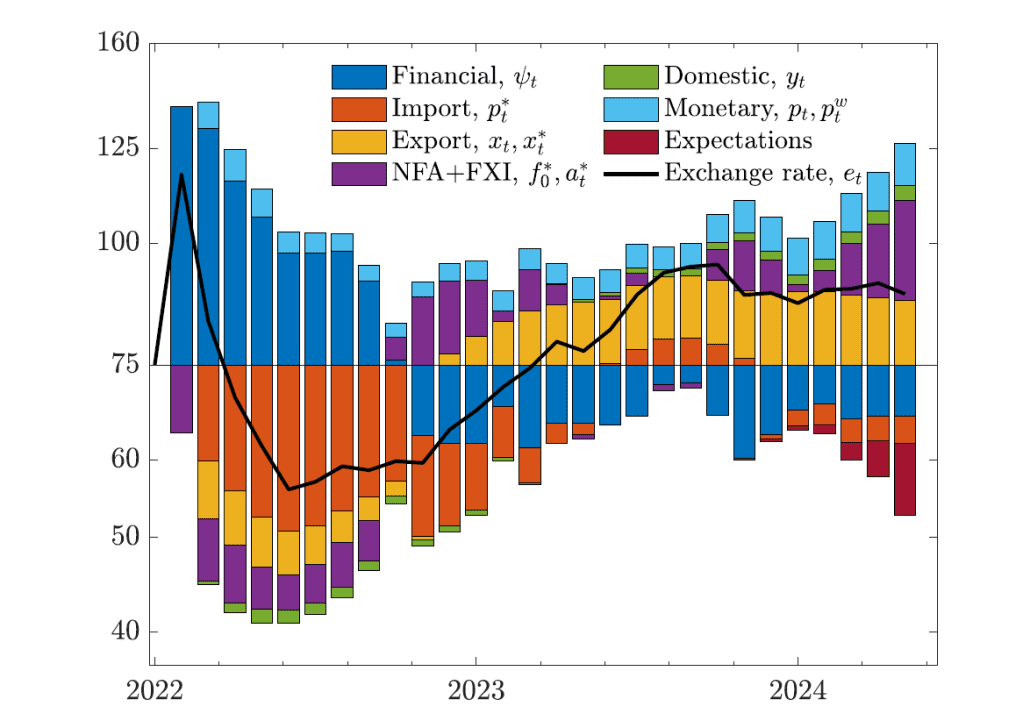

Figure 2: Exchange rate dynamics: contribution of shocks and policies

The decomposition in Figure 2 shows that the large initial depreciation—around 50 per cent—was driven mainly by financial shocks and capital outflows, mitigated by FX interventions using remaining reserves. High energy prices and import compression subsequently generated large trade surpluses that appreciated the rouble, allowing Russia to unwind early household-focused repression and rebuild reserves. A second wave of repression, now targeting exporters through mandatory FX sales, emerged in late 2023 to stabilise the exchange rate as export revenues weakened and fiscal pressures increased.

Overall, the analysis suggests that currency-market financial repression should not be viewed as a general stabilisation instrument under sanctions or sudden stops. Instead, it functions primarily as a redistributive or fiscal tool, especially when sanctions heighten financial segmentation and intensify FX-demand pressures. For macroeconomic stabilisation, however, it remains strictly dominated by FX interventions whenever these are feasible.

Sanctions and Financial Repression in the Currency Market

Authors:

Oleg Itskhoki (Harvard University)

Dmitry Mukhin ( London School of Economics)

(paper presented at the 1st Economic Policy: Papers on European and Global Issues Conference)

Watch the recording of the session

Downloads

Discussants slides