Work in Wartime Ukraine

Ukraine’s labour market shows surprising resilience to massive wartime shocks, though frontline regions suffer deep and lasting damage.

Russia’s full-scale invasion since February 2022, has subjected Ukraine’s labour market to one of the largest combined supply and reallocation shocks in recent history. Millions have fled abroad or have been internally displaced, hundreds of thousands have been mobilised, and infrastructure attacks have repeatedly disrupted economic activity. Understanding how employment has adjusted under these conditions is central for reconstruction planning and offers lessons for other economies facing sudden labour shortages and spatial reallocation. Despite extraordinary shocks, labour-market adjustment turned out to be more resilient than expected, although regional scars are profound.

Giacomo Anastasia (Columbia University), Tito Boeri (Bocconi University), and Oleksandr Zholud (National Bank of Ukraine) draw on an unprecedented range of wartime data – household and enterprise surveys, administrative data from firms reports, high-frequency job-platform records and data on air-raid alarms – to examine labor-market functioning since February 2022. Their research represents the first comprehensive analysis of how a modern labor market operates during a major interstate war fought on its own territory, combining descriptive evidence with estimates of how efficiently workers and vacancies are matched across regions experiencing different conflict intensities.

The scale of disruption is staggering. On the supply side, the civilian labor force in government-controlled territory shrank by an estimated 22% (range: 17–28%) relative to 2021. Roughly 2.8 million workers were lost through refugee outflows, another 500,000-600,000 through mobilization, with additional declines from casualties and reduced participation. On the demand side, firm-turnover data combined with pre-war productivity levels imply private-sector labor demand fell 11–17% in the first three post-invasion years. Online vacancies more than halved in the first year. Yet unemployment, which exceeded 20% in 2022, had fallen to around 13% by 2024, only slightly above its pre-war level of about 9% (according to estimates by the central bank, since no regular labor force survey has been conducted since 2022).

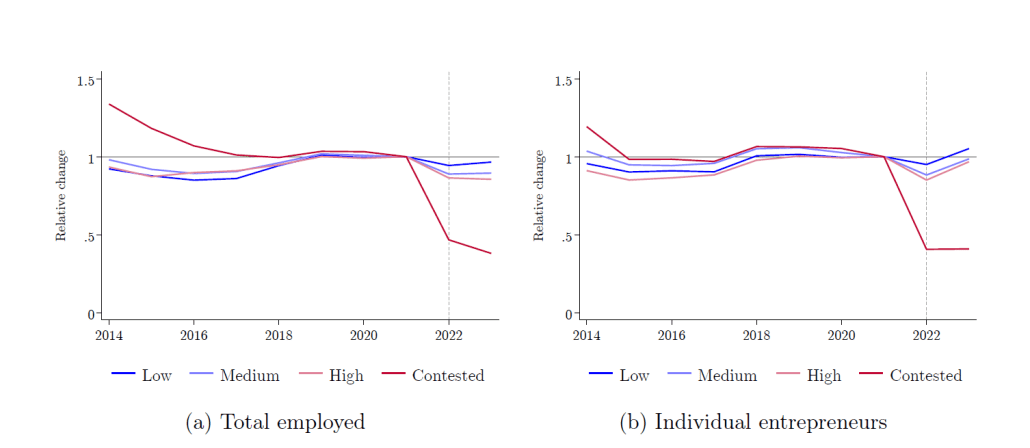

Aggregate figures conceal severe regional divergence. Using air-raid alarm data, the authors classify oblasts into low, medium and high exposure, plus contested territories.

Figure 4: Employment by exposure (duration of alarms), normalized to 2021 Source: SSSU.

In low-exposure western oblasts, enterprise employment remains close to 2021 levels. In high-exposure regions, it dropped by one-fifth. In contested areas, employment collapsed to less than half pre-war levels. Online vacancy and job-seeker flows shifted decisively away from heavily bombed areas; in several frontline oblasts both flows fell to minimal levels. Sectorally, defense-related manufacturing and services gained employment, while mining, transport, accommodation, and other consumer-facing activities contracted sharply.

A central contribution of the paper is the systematic measurement of Ukraine’s job-matching process during wartime. Using high-frequency data from the job-search platform Work.ua, Ukraine’s largest job-search platform, the authors estimate that the efficiency with which workers and jobs find each other fell by around 15% after the invasion – significant but smaller than declines seen in some advanced economies during the 2008-2009 global financial crisis.. The drop is highly uneven: western regions see declines of 4–8%, while eastern and southern oblasts nearer the front experience falls of 18–24%. Areas with more frequent or persistent air-raid alerts have significantly worse matching outcomes even after accounting for region, occupation and time effects. The time it takes to fill a vacancy rose by roughly one extra day in relatively safe oblasts and more than three days in heavily exposed ones. Sectors too showed heterogeneous matching efficiency declines.

Survey evidence sheds light on how workers and firms adapted. A substantial share of firms report expanding recruitment to underrepresented groups (for example, including women in traditionally male occupations). Employers in more exposed regions are more likely to hire internally displaced persons and older workers. Remote work is more prevalent in high-risk areas, and many refugees abroad report working remotely for Ukrainian firms, maintaining ties that could facilitate future return.

Wage-setting proved remarkably flexible. Real wages declined by about 20% before recovering above pre-war levels by 2024. Both the wages firms offered and the wages workers requested decreased, and the wedge between them narrowed after an initial spike, supporting reallocation. Notably, there is little evidence of wage premiums compensating workers in high-risk regions – likely reflecting collapsed productivity in frontline areas combined with limited geographic mobility. In some technical and professional occupations, jobseekers’ wage expectations continue to exceed posted offers, signaling persistent mismatches and a risk of further skilled emigration.

An important caveat is that the analysis focuses primarily on the formal civilian labour market in government-controlled territories, with little visibility into informal work or conditions in occupied territories. Indeed, studying labor markets through the fog of war presents inherent challenges: data are incomplete, measurement is imperfect, and many moving parts overlap. Their contribution is therefore primarily descriptive – documenting how markets functioned, what patterns emerged, and which mechanisms operated under extreme conditions.

Looking ahead, the authors argue that repairing longer-term human-capital damage – including lost schooling, trauma, health impacts and an enlarged diaspora – will require policies well beyond standard labour-market instruments. Priorities include reintegrating potentially up to one million veterans, sustaining higher female and older-worker participation, supporting workers with war-related disabilities and designing measures to encourage the return or remote engagement of skilled emigrants. With current Ukrainian average wages representing only 26% of Polish levels and 11% of German levels, outmigration pressures remain intense. The evidence suggests that while Ukraine’s labour market has adapted remarkably under extreme pressure, without sustained investment in human capital and inclusive employment the scars of war could constrain reconstruction for decades.

A Wartime Labor Market: The Case of Ukraine

Authors:

Giacomo M. Anastasia (Columbia University)

Tito Boeri (Bocconi University)

Oleksandr Zholud (National Bank of Ukraine)

(paper presented at the 1st Economic Policy: Papers on European and Global Issues Conference)

Watch the recording of the session

Downloads

Discussants’ slides